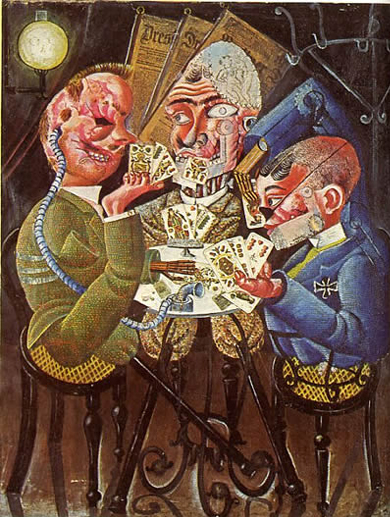

It begins so promisingly. Our hero, silhouetted against a brightening dawn sky, stares boldly into his future. He is every German mother's dream, circa 1912, of how her son might turn out: granite-jawed, pure in mind and body, wearing the hiker's gear popularised by the Wandervogel movement. The young Otto Dix, painting himself in the true German style, Durer crossed with Holbein, prepares for his long passage through life. Things, however, do not go quite according to plan. The projected walk turns out to be downhill all the way.

''Otto Dix 1891-1969'', at the Tate Gallery, is not so much an exhibition as an odyssey in pictures. It tells the story of a journey which takes in Flanders during the Great War; Dresden, Berlin and Dusseldorf during the years of the Weimar Republic and the rise of the National Socialist Party; and which winds to a conclusion with Dix in exile on the shores of Lake Constance, branded as a traitor to the national interest by the Nazis, subsiding into an undistinguished old age. The quality of Dix's art, through all this, is uneven: sometimes piercing, sometimes anodyne. But as a story, ''Otto Dix'' has a lot going for it: war, sex (lots of sex) and political intrigue. And it demonstrates that he was capable, if sporadically, of living up to his own ideals. ''Artists shouldn't try to improve and convert,'' Dix said late in life, ''they're far too insignificant for that. They must only bear witness.''

This show also suggests that Dix's reputation as a radical may not have been wholly deserved or even sought by the artist himself. He is revealed as something of a traditionalist (although the uses to which he put tradition were, frequently, pretty startling), as an artist in the old northern-European mould: a painter...