Andrew Graham-Dixon examines the Late Picasso paintings, prints and drawings on show at the Tate Gallery

Shortly after Picasso's death, in 1973, his long-time friend Douglas Cooper delivered the most famous verdict on the artist's later work: "These are incoherent doodles done by a frenetic dotard in the anteroom of death." "Late Picasso", at the Tate, allows the greatest painter of the twentieth century several anterooms through which to approach the inevitable, unpalatable truth of his own mortality. The exhibition comprehensively demolishes Cooper's bitter and shallow one-liner; it also overturns just about ev¬ery existing preconception about the way in which great artists are supposed to grow old.

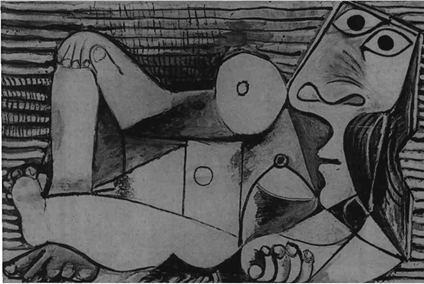

Late Picasso is graceless, scurrilous, irreverent. He is frankly obsessed with violence, with sex, and with the carnally suggestive capacities of line, colour and texture. The paintings are ugly, awkward, brutal; late Picasso rages, fantasises, caresses and disturbs, cultivating a style that flouts all notions of aesthetic propriety and tee¬ters constantly on the brink of mere slapdash.

The great theme of Picasso's later art is — as it had been in the first decade of the century, with Les Demoiselles d'Avignon — the female nude. Picasso's late nudes arc monumental, intimidat¬ing harpies, who fix you with a wonky, basilisk glare. Near the start of this show, you are con¬fronted by a Seated Nude of 1959, which predicts much of the art to follow. Subjected to extreme pictorial violence, refracted throught the geome¬tries of what seems like a late, late version of the Cubist kaleidoscope, her body has been mon¬strously dislocated. Her right breast emerges from underneath one armpit, neighboured by a thick, brushy patch of underarm hair. Following the arm that jacknifes up and back behind her head, you notice that it elides with the line of her right cheek, stretching it into...