Andrew Graham-Dixon on the ascendancy of Goldsmiths'

The old stereotype of The Artist - the tubercular, unshaven figure everyone has in their mind's eye - has taken something of a beating in recent years. It is common knowledge that, as Joseph Beuys put it in one of his aphoristic jottings, ''Kunst = Kapital''. Even moderately successful artists live in nice houses and drive nice cars like ordinary rich people.

Art has come to represent, among other things, a good career opportunity, and all the signs are that the average art student has twigged this. Degree show prices are high (higher than prices at a lot of commercial galleries), and degree shows themselves have undergone something of a metamorphosis. Messy experi-mentation is out. Neatness and professionalism prevail.

The pre-degree show is a relatively new phenomenon. Last week the Chisenhale Gallery staged ''Countdown'', an exhibition of work by six MA students from Goldsmiths' School of Art which exemplified the trend. Countdown to what? Success, with luck. T-minus not long and counting.

Goldsmiths' has, for some time now, epitomised the New Professionalism sweeping the art schools. Goldsmiths' students get places, and they get there fast. One of the artists in ''Countdown'', Nicholas May, has already been earmarked for a spot in Doris Saatchi's collection; another, Patrick McBride, will represent Great Britain in the open section of the Venice Biennale (the Aperto) this summer.

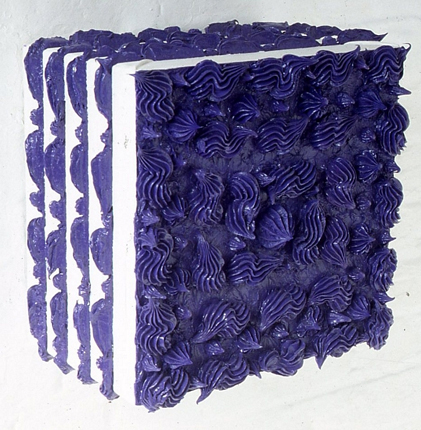

What distinguishes Goldsmiths' art from the product of every other British art school is perhaps, above all, its determination to be relevant. In Patrick McBride's case relevance takes the form of weird, sinis-ter-baroque installation art. His contribution to ''Countdown'', Blindfold, is a Brobdingnagian collar, swathed in lace-trimmed velvet and suspended from the ceiling on meathooks. Funereal and kinky at the same time, it could have been a massively enlarged prop...