WILLIAM HAZLITI once remarked that Turner's paintings were "pictures of nothing, and very like". He meant the late works — those vortices of light or primal oceanic upheavals that swirl in the roomful of late Turners at the Clore — and he meant it as an insult.

Since then modernism has intervened, and pictures of nothing are labelled abstract art. Recent years have seen a series of critical attempts to enlist late Turner as a modern artist stranded in the nineteenth century, a revolutionary whose visionary ideas — hampered by the prevailing pictorial and iconographie conventions — initiated a tradition that would culminate in the abstractions of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

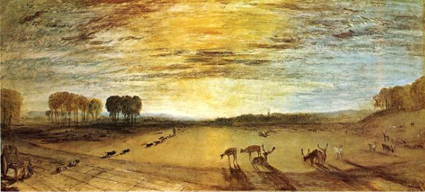

The new arrangement of the Turner Bequest reads like an extended argument against his modernity — both in the hanging of the paintings and, perhaps surprisingly, in the design of the exhibition space (it feels like a cross between Soane's nineteenth century Dulwich Art Gallery and the Yale Centre for British Art). In this classical, academic setting the pictures are accompanied by brief essays which explain Turner's often arcane iconography, point out his self-conscious imitations of the Old Masters, and quote the lines of poetry which he originally appended to his works when he showed them at the Royal Academy. The Bay ofBaiae, with Apollo and Sibyl invites you to gaze past its two diminutive human protagonists into the lucid depths of an ideal landscape, the world turned to honey by Turner's sun, the sails of distant ships reflected in the clear expanse of a sea that stretches to infinity. The text on the wall transforms the picture from wistful travelogue into allegory, a moralising contrast between the unfading beauty of nature and the folly of human ambitions for permanence. Turner's painting tempts you to put on sunglasses and...