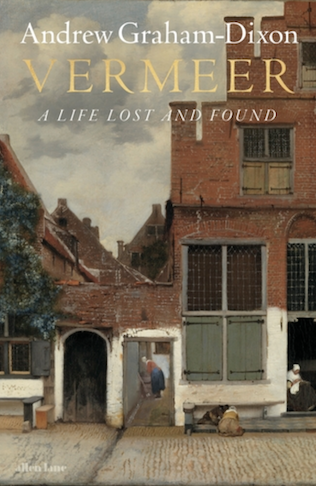

Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found

When Vermeer’s pictures for Maria de Knuijt and her husband Pieter were dispersed at auction in 1696, three tronien or “character portraits” were the last lots sold. Lot 38, the first of the trio to go under the hammer, was advertised as the best of them. Described in the auction catalogue as ‘a tronie in antique dress, uncommonly artful’, this picture can be confidently identified as the Girl with a Pearl Earring now in the collection of the Mauritshuis. The girl portrayed is certainly wearing ‘antique dress’, in the form of an oriental turban fashioned from scarves of yellow and ultramarine blue, of the kind in which Dutch artists of the period were apt to clothe biblical characters. The picture is so beautifully painted that its every last detail proclaims Vermeer’s uncommon artfulness. The expression on the girl’s face is hauntingly immediate, the artist’s treatment of light and shade beguilingly delicate. The painting of the highlights in her limpid light-brown eyes is brilliant, so too the recreation of the reflections trapped in the pearl of otherworldly size that she wears as an earring.

Not only does the girl seem on the point of utterance, she has the air of someone about to say the most urgent thing they have ever said. It is a picture of a moment preserved in stillness, but which is also full of motion. The girl’s feelings are shifting and turning, in transition. She is moving in the literal sense too, turning around to look someone in the eye. She has only just realized who that someone is.

To understand the painting we need to know three things: the identity of the real live girl who sat for it; the identity of the character in the Bible whose part she plays; and the identity of the person to whom she turns, as if to speak. The first two are fairly easy to establish. Once they are known, the third follows logically and all becomes clear. The Girl with a Pearl Earring has a reputation for being insolubly enigmatic but in truth it is one of Vermeer’s most straightforward pictures. Its messages are piercingly direct, and demanding.

The painter shows us a girl of about twelve, maybe thirteen. Vermeer’s eldest daughter Maria was born in 1654, but why would he paint a biblically inspired portrait of his own child for the house of his patrons? Considering that the picture was made for Maria de Knuijt and her husband it is a fair assumption that the sitter was someone they knew and cared about. There is only one plausible candidate, namely their daughter, Magdalena van Ruijven.

Magdalena was born in October 1655, so would have reached the age of twelve in the autumn of 1667. Assuming that she participated in the Collegiant movement she would likely have solemnized her commitment to Christ at that age, possibly undergoing baptism by full immersion at the summer gathering at Rijnsburg the following year. Vermeer’s portrait of her in character may have been painted to mark that rite of passage. It could have been done either before or after the baptism itself, so was probably completed sometime in 1667 or 1668.

If the girl who sat for the painting is Magdalena van Ruijven, which figure in the Bible might she reincarnate? Again, there can only be one answer. Magdalena had been named for Mary Magdalene, like her grandmother before her. There seems to have been a family tradition of venerating Mary Magdalene, to judge by the fact that one of the first pictures commissioned from Vermeer by Magdalena’s mother, the Sleeping Maid, was directly inspired by her legend. So the Girl with the Pearl Earring brings us face to face with Magdalena van Ruijven in the persona of Mary Magdalene, follower of Christ.

Towards whom does the girl in the picture turn with such depth of feeling? The answer to the last of our three questions is to be found in that passage in John’s Gospel where Mary goes to Christ’s tomb in search of his body. A text close to the hearts of many Collegiant women, it is worth quoting in full. The Girl with the Pearl Earring is an imaginary representation of the Magdalene as she appears in the words of its final verse, emphasized here in italics:

But Mary stood without at the sepulchre weeping: and as she wept, she stooped down, and looked into the sepulchre, and seeth two angels in white sitting, the one at the head, and the other at the feet, where the body of Jesus had lain. And they say unto her, Woman, why weepest thou? She saith unto them, Because they have taken away my Lord, and I know not where they have laid him.

And when she had thus said, she turned herself back, and saw Jesus standing, and knew not that it was Jesus. Jesus saith unto her, Woman, why weepest thou? whom seekest thou? She, supposing him to be the gardener, saith unto him, Sir, if thou have borne him hence, tell me where thou hast laid him, and I will take him away. Jesus saith unto her, Mary. She turned herself, and saith unto him, Rabboni; which is to say, Master.

Vermeer conjures up Mary Magdalene in this instant, as she turns back towards the gardener whom she has just understood to be Jesus Christ. The look on her face expresses dawning recognition and wonder, mingled with awe, humility and love. There is the suggestion of tears recently shed in her bright, liquid eyes. The pearl at her ear is impossibly large because it is no simple jewel but a reflection of the state of her soul, bursting with joy and irradiated with divine light. She is the first person in all of history to see the risen Christ, to speak with him, to grasp the enormity of all that his presence embodies. Once she has got over the sublime shock of it, she will tell the rest of the world what she, and only she, has been given to know.

To have been christened Magdalena was to have been charged with preserving that meeting in the memory. Vermeer’s picture was there to summon and sustain that moment daily, directing Magdalena’s prayers and placing her always in the presence of Christ, near his empty tomb. The picture would also have spoken powerfully to those who visited or prayed in the house where she lived with her parents. Deeply affecting, yet conceived in a spirit of ruthless conceptual purity, it accomplishes something that several of the other pictures painted for those rooms could only represent in terms of desire or longing: the return to earth of the resurrected Christ.

Magdalena as Mary Magdalene uttering the word ‘Master’ brings Christ by implication into the same room as her and therefore us. He remains invisible, but nonetheless present as the focus of her gaze. This turns the picture into a kind of challenge. If we are looking at her, and she is looking at Jesus, then we must be standing in his shoes.

Publisher: Penguin (October 2025)

Language English

ISBN: 978-1-846-14710-4

Product Dimensions: 24 x 16 x 4 cm